Promises kept, windfall banked. Reforms next?

- The budget deficit is expected to be $36.9 billion(1.5% of GDP), an improvement of $41.1 billion from the Pre-election Economic and Fiscal Outlook (PEFO). The deficit is expected to widen modestly to $44.0 billion (1.8% of GDP) in 2023-24, $12.5 billion lower than PEFO. But deficits have been upgraded for 2024-25 and 2025-26.

- The Budget delivers on the expectations the Treasurer laid out in the lead up to the big day. Election commitments were fulfilled, and revenue was upgraded owing to higher-than-expected commodity prices and a stronger nominal economy.

- But the Treasurer also stuck to his commitment of outlining a bleaker economic picture. The Government expects growth to slow to just 1.5% in 2023-24. The unemployment rate is expected to increase to 4.5% and inflation is expected to remain higher for longer. Inflation does not return to the RBA’s target band until 2024-25.

- Beyond the first two years, the economic projections look optimistic. They assume several key variables, such as GDP and inflation, return to long-run averages. This presumes the inflation challenge will abate relatively quickly and that policy makers will be able to engineer a soft landing. Time will tell whether such an outcome can be achieved.

- Chalmers avoided the temptation to spend this year’s “revenue dividend”, instead choosing to bank most of it. Indeed, the Budget spends very little of the $144.6 billion of temporary tax windfalls that have flowed into the Treasury chest.

- The revenue tailwinds quickly ran out of puff as the structural budget challenges become ever present over the medium term. The detail reveals structural budget deficits as far as the eye can see, averaging 2% of GDP over the medium term.

- By highlighting these issues, the Government has set the scene for economic and fiscal reform in later budgets.

- Reforms are required to ensure that the structural deficit is reduced over time, revenue is collected in an efficient way, and that the government gets value for money in its expenditure. Additionally, reforms are needed to drive productivity, which will also boost government revenue and the budget position.

- Spending and cost-of-living relief was targeted as the Government sought to make the RBA’s job easier, not harder, by limiting fiscal stimulus during a time of heightened inflation. This included a $7.5 billion cost-of- living package, focused on cheaper childcare, cheaper medicines and lifting the supply of affordable housing.

- The Government also stumped up capital into investment funds to bankroll future spending on affordable housing, the energy transition, the regions, and disaster relief.

Main themes

The budget deficit is expected to be $36.9 billion (1.5% of GDP), an improvement of $41.1 billion on the forecast made in the April Pre-election Economic and Fiscal Outlook (PEFO).

The deficit is expected to widen modestly to $44.0 billion (1.8% of GDP) in 2023-24, which is lower than PEFO by $12.5 billion. But deficits are larger than laid out in PEFO for 2024-25 and 2025-26.

In handing down this budget – his first – Federal Treasurer Jim Chalmers faced three key issues. The need to address structural budget deficits through fiscal repair, bracing for the near-term economic slowdown and dealing with the cost-of-living crisis.

Only one of these issues is arguably more persistent and long term – that is, addressing structural budget repair. This is because the budget faces big, persistent spending pressures, especially in areas like the NDIS, aged care, defence, social welfare and health. Higher global interest rates have also led to a sharp increase in expected interest repayments on government debt. Highlighting the depth of this issue is the fact that from 2024-25, the structural deficit averages around 2% of GDP – this is clearly not a long term sustainable fiscal position.

Chalmers to his credit has avoided the temptation to spend this year’s “revenue dividend”, instead choosing to bank most of it. Indeed, the Budget spends very little of the $144.6 billion of temporary tax windfalls that have flowed into the Treasury chest.

No doubt the monetary-policy backdrop also loomed large over the decision making, leaving Chalmers with little wriggle room. Stimulating the economy would have only added fuel to inflation and put more pressure on the RBA to hike the cash rate to bring inflation under control.

Much of the spending flagged, therefore, is targeted. This targeted approach minimises the impact on inflation.

Notable in the Budget was that the Government delivered on its election promises. It also kept spending responsible, banking most of the tax windfall that saw a vast improvement in the bottom line. By delivering on their election promises, goodwill and trust with the Australian public can be fostered – a good starting point for economic and fiscal reform in future budgets. So, whilst this Budget was lacking in large scale reform measures, the Government perhaps has reform in its sights for future budgets. This will be welcome news for economic policy wonks, who have been calling for large scale reform of Australia’s revenue and spending pressures for many years.

The strong improvement in the fiscal position compared with the PEFO means the underlying cash deficit is forecast to be $41.1 billion better in 2022-23, taking the estimate to$36.9 billion. A large improvement has also been forecast for 2023-24, of $12.5 billion, for an underlying budget deficit of $44.0 billion.

There are revenue improvements across the out years, but the improvement in the bottom line is concentrated in the near term. The boost to the bottom line is temporary and brief. The nominal economy has grown strongly – 11% last financial year – and is set to expand by 8% in 2022-23. Unemployment has dropped. Commodity prices have spiked. This combination has helped drive an improvement in the bottom line.

But over the medium term, it will be tougher for the Government to deliver significant improvements to the Budget balance without reform because economic conditions are deteriorating. The global economic picture is darkening, and tougher times lie ahead for the economy.

Economic growth will be markedly weaker in 2023-24 and unemployment will be moving higher. Inflation is elevated and more rate hikes from the Reserve Bank (RBA) are likely. There is the real risk of a hard landing in some of the major economies around the world and the path to a soft landing here at home has narrowed.

Beyond the first two years, the economic projections look optimistic. They assume several key variables, such as GDP and inflation, return to long-run averages. This presumes the inflation challenge will abate relatively quickly and that policy makers will be able to engineer a soft landing. Time will tell whether such an outcome can be achieved. For example, the Government has inflation returning to 2.5% by the end of 2024-25, while wages are expected to grow at 3.25% by 2024-25, supporting spending and economic activity. If these forecasts do not materialise and real wages continue to go backwards, the real economy may be weaker for longer, having a negative impact on the Budget.

The recent shift ahead in the economy’s fortunes, especially the nominal economy, means the Government will need to take a more active role in the future to address budget repair.

The key policy announcement was a $7.5 billion five-point cost-of-living package. The package includes cheaper childcare, expanded paid parental leave (to be phased in over coming years) and making medicines cheaper, including through new and amended Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme listings. It also makes commitments for more affordable housing (through a new accord between governments, investors and industry) and getting wages growing.

This Budget is also notable for its new investment funds, which were numerous. It includes Rewiring the Nation Fund, Housing Australia Future Fund, Powering the Regions Fund, Driving the Nation Fund and National Reconstruction Fund – amounting to over $40 billion in capital.

Biggest winners

The biggest winners are families. The cost-of-living package contains measures that alleviate pressures for families. They are centred around reducing childcare expenses, expanding paid parental leave, making medicines cheaper and delivering more affordable housing through a new accord and the Housing Australia Future Fund.

The property industry is also a winner with the New National Housing Accord – an agreement between the Commonwealth government, governments of the states and territories, investors and industry to boost housing supply and create more affordable and social housing.

The Government has also commissioned the National Housing Supply (soon to be established) and Affordability Council to review the policy settings for investment into housing, including around build-to-rent.

There are no new direct spending initiatives for businesses across all industries. But businesses are not losers. Net overseas migration projections ramp up significantly. Indeed, the forecast for 2022-23 has been upgraded sharply to 235,000, from 180,000 at the time of the March Budget. This upgrade represents extra labour supply. Labour shortages are a key issue facing businesses and some forthcoming improvement is a plus for businesses.

Another winner worth calling out is the RBA. The Treasurer refrained from spending the tax windfall and banked most of it. The RBA would have had a trickier time in bringing down inflation if Chalmers had spent the dividend. Over 90% of the dividend was banked.

Budget reform – is the Government laying the groundwork for larger reforms?

The Budget largely delivers on what the Treasurer promised. The Government has used this opportunity to implement the commitments it outlined in the lead up to the election.

However, the Budget papers underscore a serious long- term issue for Australia as the structural budget balance is expected to remain in deficit for the entire forecast period and medium-term (out to 2032-33). In fact, rather than improving, the structural budget deficit is expected to remain broadly stable at around 2% of GDP throughout the period.

This underlies the challenges that Australia faces as the population continues to demand a higher level of public spending and services, while the government doesn’t raise enough revenue to fund these expenditures in the longer-term.

To address these challenges, the Government must either reduce spending, increase revenue, or apply some combination of the two. These are not easy decisions to make and can often be difficult to get through Parliament.

The Government has sought to outline some of these longer-term challenges. This included upward revisions to key payments categories such as interest payments and the NDIS, which contribute to the deterioration in the budget position over the medium-term. Additionally, higher inflation leads to higher indexation across other areas, including Jobseeker, the Disability Support Pension and the Age Pension.

The productivity growth assumption has also been reduced from the 30-year average of 1.5% to the 20-year average of 1.2%. Productivity growth in Australia and across other developed economies has been trending lower over recent decades and has been below 1.0% in recent years. The causes of lower productivity growth are numerous and complex, including lower competition and economic dynamism, slower take up of new technologies, diminishing returns across innovations, increased importance of the services sector, higher levels of inequality, and many others.

The challenge of increasing productivity growth should not be underestimated. The impact of lower productivity growth is largely felt towards the end of the medium-term. This lowers real GDP by 1.75% by 2032-33. The underlying cash deficit is also projected to be 0.3 percentage points higher due to a lower tax take, and gross debt is subsequently projected to increase by 2 percentage points in 2032-33.

While the Government has emphasised these long-term challenges and taken some steps to improve productivity, it has not outlined a comprehensive plan to address them. These challenges are numerous and require large scale reforms across spending and revenue.

On the tax side of things, the landmark Henry Tax Review (officially Australia’s Future Tax System Review) from 2010 seems like it was delivered a generation ago and has largely laid on the shelf to collect dust. While governments have tried to implement certain measures from the review, wholesale reform across the entire system has remained a dream of policymakers.

On the spending side of things, the Budget continues to face growing pressures across many key categories, including health care, NDIS, aged care, the retirement income system, the environment, defence, education and training, and other key areas.

By drawing attention to many of these pressures, the Government appears to be sowing the seeds for more substantial reform in future Budgets. The Treasurer alluded to this in media commentary prior to the Budget, noting that “We are encouraging people to see this as the first of three or maybe four Budgets in this parliamentary term” and that “This Budget will begin the long hard road to Budget repair before we arrive at the final destination”.

The Budget, inflation and the RBA

We expect the RBA to raise the cash rate to a peak of 3.60% early next year, from the current cash rate of 2.60%. Interest-rate markets expect the cash rate to rise to a higher rate of around 4.20% and for this peak to occur later in 2023.

Today’s budget does little to stoke inflation with much of the tax revenue windfall banked and spending mostly very targeted. Additionally, most of the $9.8 billion of net impacts due to policy decisions occur in the final two years of the forward estimates, when inflation is expected to have declined from the current high levels.

Inflation is forecast to be more persistent that at PEFO. Annual inflation is expected to peak at 7.75% in late 2022, before moderating gradually to 3.5% by June 2024. Inflation is forecast to fall to the mid-point of the RBA’s 2-3% band by June 2025 and then stay there.

The Government’s peak for inflation matches the RBA’s forecasts (both timing and size). It is also consistent with our own view.

However, the Government is betting on a faster decline in inflation in 2022-23 compared with the RBA. We think the decline is too rapid and too early. The Government has inflation returning to the middle of the band in 2024-25; we do not expect inflation to return to the band until late 2025 – and even then – just brushing the top of the band only.

Budget outlook

A tale of two horizons

Elevated commodity prices and higher than expected price and wage inflation have underpinned a sizable improvement in the budget balance. This improvement is front loaded, leading to significant improvements in the bottom line in 2022-23 and 2023-24.

In the final year of the forward estimates period (2025-26) cost pressures resulting from higher global interest rates and strong growth in social service programs begin to dominate. A slower productivity assumption also contributes to lower tax revenue and ultimately larger deficits. Over the medium term, the near-term improvement shifts to a deterioration in the budget bottom line.

This deterioration persists as the stark reality of a structural budget deficit emerges. In fact, the Budget shows that in the absence of any changes to policy, the structural budget balance will be in a deficit of around 2% of GDP on average over the medium term.

While the Government has announced several tax integrity measures which raise significant revenue, and a number of savings measure to control costs, these changes come nowhere near to addressing the structural budget balance issue.

This Budget sets the scene for economic and fiscal reform. Without economic reform to deliver greater productivity and fiscal reforms to deliver a more efficient tax base, the Government will continue to live beyond it means.

If this occurs, Australia’s AAA credit rating will be in jeopardy during future recessions. A credit rating downgrade could lead to higher interest costs for the Government, and subsequently, taxpayers.

Further, high and increasing debt levels reduce the capacity for governments to provide support in times of economic stress in the future. Australia’s strong budgetary position was a key pillar which assisted the Government to provide the level of support delivered during the pandemic.

Budget bottom line

Over the forward estimates, the budget deficit is projected to increase from $36.9 billion (1.5% of GDP) in 2022–23, to $49.6 billion (1.8% of GDP) in 2025-26. The sum of the budget deficits over the forward estimates is projected to total $181.8 billion.

Total receipts (including tax and non-tax receipts) as a share of GDP are more volatile, increasing from 24.5% of GDP in 2022-23 to 25.2% of GDP in 2025-26. Total receipts are projected to be 26.0% of GDP in 2032-33.

The tax-to-GDP ratio is expected to go from 22.7% in 2022- 23 to 23.4% by 2025-26. It is expected to reach 24.1% of GDP by 2032-33, which is above the previous Government’s tax cap of 23.9%. The improvement in the tax-to-GDP ratio reflects bracket creep – higher wages means that individuals will be pushed into higher tax brackets and, on average, pay a larger share of their income in tax. This occurs even with Stage 3 tax cuts remaining unchanged.

Payments as a share of GDP are expected to increase from 25.9% in 2022-23 to 27.1% in 2025-26. By 2032-33, payments are projected to be 27.9% of GDP.

Stronger budget over the forwards

Since the PEFO, the budget balance has improved by $42.7 billion over the four years to 2025-26.

Changes to the bottom line were driven by the larger nominal economy, which contributed around $52.5 billion of the improvement in net terms. Revenue (predominately company and personal income tax revenue) was revised up by $144.6 billion over the four years. This was partly offset by a $92.2 billion increase in payments resulting from higher indexation of income support payments and the higher public debt interest.

Government policies worsened the bottom line by around $9.8 billion over the four years. In 2022-23 the net impact of Government measures was a fiscal expansion of $1.1 billion. This fiscal expansion grows to $7.4 billion in 2025- 26, as the new programs, such as cheaper childcare and cheaper medicines, reach maturity.

Budget to deteriorate over the medium term

The improvement in the bottom line is expected to be short lived. The budget deficit is expected to be 1.9% of GDP by the end of the medium term, a deterioration of 1.2 percentage points since PEFO. Three factors underpin this deterioration.

Firstly, the lower productivity growth assumption lowers real GDP and reduces the size of the tax base. This contributes around 0.3 percentage points of the deterioration in the bottom line.

Secondly, applying higher yields on government debt contributes around 0.6 percentage points of the deterioration in the budget bottom line. The assumed yield on 10-year bonds issued over the forward estimates is 3.8%, compared with 2.3% at PEFO. The 10-year yield is then assumed to rise to 4.3% by the end of the medium term, around 70 basis points higher than projected at PEFO.

Finally, applying revised NDIS costs, in line with an updated actuarial assessment, increases the underlying cash deficit by 0.7 percentage points of GDP.

The fiscal strategy

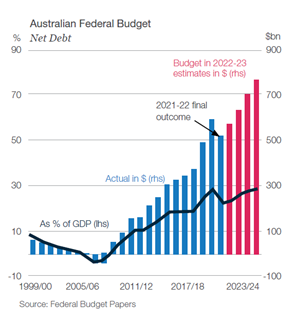

Gross and net debt follow the trajectory of the budget bottom line – improvement over the forward estimates but then deteriorating over the medium-term. Interest payments as a share of GDP are expected to be around the long run average of 1.0% of GDP by 2025-26.

Gross debt is estimated to be 37.3% of GDP ($927.0 billion) by the end of 2022-23, lower than the estimate of 42.5% of GDP ($977.0 billion) at PEFO. However, gross debt is projected to stabilise at 46.9% of GDP by the end of the medium term – this is around 6.7 percentage points higher than at PEFO.

Net debt remains lower than estimated at PEFO across each year of the forward estimates. It is expected to worsen over the medium term to be 31.9% of GDP by the end of 2032-33. This is around one percentage point higher than at PEFO.

Interest payments as a share of GDP in 2022–23 and 2023–24 are expected to remain broadly consistent with PEFO. Over the remaining forward estimate years, interest payments as a share of GDP are expected to be higher than at PEFO as higher borrowing costs more than offset the expected lower issuance of Australian Government Securities (AGS). By 2025–26, interest payments as a share of GDP rise above the 30-year average of just under one per cent.

Note that the budget estimates assume a weighted average cost of borrowing of around 3.8% over the forward estimates, compared with around 2.2% at PEFO.

The fiscal strategy is “not adding to inflationary pressures and to begin budget repair. Over time, the focus will shift to achieving measured improvements in the budget position to stabilise and reduce gross debt as a share of the economy.”

The Government plans to do this by limiting the growth in spending and directing most improvements in tax receipts to budget repair.

Economic outlook

Real economy

Since the March Budget and the PEFO that followed soon after, the economic outlook for the Australian and the global economy has deteriorated. Inflation has proved to be higher and more persistent than expected and the global economic and geopolitical environment has become more uncertain. As central banks aggressively hike rates to control elevated inflation, the prospect of a hard landing has grown across many major economies.

The war in Ukraine has led to a spike in many key global commodities and further fuelled the inflation fire. Global supply chain disruptions continue to have an impact on inflation, despite beginning to ease from their peak levels during the pandemic.

Additionally, while global factors have accounted for much of the lift in inflation so far, domestic factors continue to grow. Strong domestic demand amid an economy that is operating beyond full capacity has contributed to rising inflationary pressures and is likely to become the primary driver of inflation going forward.

Australia has not been immune to these factors. The Reserve Bank (RBA) has embarked on the most aggressive hiking campaign since 1994 as it seeks to control elevated inflation. The RBA hiked rates by 250 basis points since May 2022 and more hikes are expected.

These factors have all impacted the economic outlook and contributed to a downgrade in the economic forecasts over the forecast years of 2022-23 and 2023-24.

While growth is expected to be robust in 2022-23 at 3.25%, it is expected to weaken in future years. Real GDP growth has been downgraded to 1.5% over 2023-24, down from 2.5% in PEFO. Looking further into the forward estimates, the Government expects economic growth to pick up and be closer to trend, at 2.25% in 2024-25, and 2.5% in 2025-26.

Overall, this is a bleaker economic picture than was painted less than six months ago. A more downbeat global outlook contributes to the downgrade. However, while the economic outlook has been downgraded in the near term, the economy is expected to return towards trend levels over 2024-25 and 2025-26.

*GDP data are percentage change on the previous year. The consumer price index, employment and wage price index are through the year growth to the June quarter. The unemployment rate is for the June quarter.

This presumes that the significant inflation challenge that Australia currently faces will abate relatively quickly and that policy makers will be able to engineer a soft landing. Time will tell whether such an outcome can be achieved.

On inflation, the Government expects inflation to peak at around 7.75% in the December quarter of 2022. This is significantly higher than the forecasts at PEFO. Inflation is expected to be 5.75% in 2022-23, before declining in 2023-24 and 2024-25.

However, inflation is expected to be higher for longer and is not expected to return towards the RBA’s 2-3% target band until 2024-25, pushed out one year from 2023-24 in PEFO.

The weaker economic outlook is expected to impact employment and the unemployment rate is expected to increase. Remember, the labour market has been one of the star performers since the pandemic hit and the unemployment rate is currently at 3.5%, around its lowest level in 50 years.

The Government expects the unemployment to rise as slower economic growth leads to less job creation and softer demand for workers. The unemployment rate is forecast to increase to 4.5% in 2023-24, up from 3.75% forecast at PEFO. The unemployment rate is expected to remain at 4.5% in 2024-25, before declining to 4.25% in 2025-26.

This is more optimistic than our view. We expect the unemployment rate to increase to 4.8% in 2023-24, and 5.3% in 2024-25.

Australia has remained a desirable location for immigrants and migration has returned faster than expected since the opening of the international border. As a result, net overseas migration (NOM) is forecast to return to pre-pandemic levels much quicker than previously expected. NOM is projected to rise from 150k in 2021-22 to 235k in 2022-23 (in line with pre-pandemic trends). In contrast, in the March Budget, NOM was expected to gradually return to 235k by 2024-25.

Upgrades to wages growth at odds with other labour market changes

Despite a downgrade to the employment outlook, a higher unemployment rate, greater labour supply due to an increase in NOM, and a downgrade to real GDP, wages growth (measured by the Wage Price Index) has been upgraded relative to PEFO.

Wages growth is expected to pick up to 3.75% in 2022-23 and remain there in 2023-24, compared to 3.25% over the same years at PEFO. Wages growth is then expected to decline to 3.25% and 3.5% in 2024-25 and 2025-26, respectively.

The upgrades seem somewhat at odds with other forecast changes to the labour market. The Government has made “getting wages moving again” a key part of its agenda and outlined recent actions taken to support higher wage outcomes for low paid workers and policies it claims will “make it easier for employees and businesses to come together and reach agreement on wages and conditions.”

The outcome of such measures is difficult to ascertain. However, the Government appears to be forecasting that the measures will increase wages growth despite other changes across the labour market. Time will tell whether the Government’s policies have the desired impacts.

Nominal economy

Despite a deteriorating real economic outlook, a key factor for the budgetary position is the nominal economy. This has a big impact on government revenues and the total tax take.

Due to higher-than-expected commodity prices and higher inflation, growth in the nominal economy has been revised higher. Nominal GDP growth is expected to 8.0% in 2022-23, revised up significantly from only 0.5% at PEFO. Nominal GDP growth is then expected to fall by 1.0% in 2023-24. This is due to projected falls in commodity prices and Australia’s terms of trade.

As has been the case in budgets over recent years, commodity prices (including iron ore, coal, and LNG) are expected to decline from their current high levels towards longer-run projections by the end of the March quarter 2023. This contrasts with the March Budget, which assumed commodity prices would decline by the end of the September quarter 2022.

Supply-chain disruptions and the war in Ukraine have impacted the supply/demand dynamics of many key commodities and contributed to prices remaining elevated. Prices are likely to remain relatively elevated as these disruptions are gradually worked through. The ‘glide path’ methodology means that there is a good chance that tax collections will be higher than expected in future years.

The severe flood across many parts of Australia in October 2022 are expected to lead to a 0.25 percentage point reduction in GDP growth in the December quarter of 2022. Additionally, the floods are expected to add 0.1 percentage points to inflation in the December quarter of 2022 and the March quarter of 2023 though higher fruit and vegetable prices.

Budget overview – key measures

New investment funds

- The Government has unveiled a raft of new investment funds, which will act as seed funding for future expenditures. The investment income from these funds will be used to finance future spending, rather than financing the spending now using debt.

- Housing Fund

- $10 billion will be invested in the Housing Australia Future Fund to generate returns to fund the delivery of 30,000 social and affordable homes over five years and allocate $330 million for acute housing needs.

- In the first five years, investment returns will be used to fund repairs and maintenance for remote indigenous communities, crisis and transitional housing options for women and children fleeing domestic violence and homelessness and to build more housing for veterans experiencing homelessness.

- Rewiring Australia Fund

- $20 billion will be provided to establish ‘Rewiring the Nation’ to expand and modernise the electricity grid, unlock new renewables and drive down power prices.

- Funding will be used to provide concessional loans and equity to invest in transmission infrastructure projects that will help strengthen, grow and transition the electricity grid.

- The policy will have a net positive impact of $158.1 million on the underlying cash balance over the forward estimates as interest revenue on investments is expected to offset spending measures.

- Powering the Regions Fund

- The Government will establish the Powering the Regions Fund with $1.9 billion allocated from the uncommitted funding from alternative funds.

- Initial funding includes $5.9 million to support reforms to assist industries with the transition to net zero and $3.3 million for further design and development of the Powering the Regions Fund.

Spending measures

- Families

- An additional $531.6 million over four years and $619.3 million per year thereafter to enhance and provide more flexibility to the paid parental leave scheme.

- From 1 July 2023 the paid parental leave scheme will be flexible for families so that either parent is able to claim the payment. Parents will also be able to claim weeks of the payment concurrently so they can take leave at the same time.

- From 1 July 2024 the scheme will be expanded by two additional weeks per year until it reaches 26 weeks from 1 July 2026.

- $4.7 billion over four years to improve childcare affordability by increasing the childcare subsidy rate for single child families to 90% for family incomes of up to $80,000. The subsidy is tapered by 0.2% for every $1,000 of family income above $80,000.

- The childcare subsidy has increased for all families with combined incomes of less than $530,000.

- Aged care

- $2.5 billion over the four years to “fixing the aged care crisis” and reforming the aged care system. This includes increasing staffing requirements for carers and registered nurses, mandating minimum daily care minutes and nutrition standards and enforcing transparent reporting from aged care providers.

- $540.3 billion over four years to improve the delivery of aged care services and respond to the final report of the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety.

- $845.4 million in 2023-23 to support older Australians and the aged care sector with managing the impacts of COVID-19. Majority of funding directed towards aged care providers for additional costs incurred during COVID-19 outbreaks.

- Business initiatives

- $15.1 million in funding will be provided over two calendar years commencing in 2023 to extend the Small Business Debt Helpline and the New Access for Small Business Owners Programs to support the financial and mental wellbeing of small business owners.

- Climate spending and disaster support

- $157.9 million over six years and $1.1 million per year thereafter to support the implementation of the National Energy Transformation Partnership, which will deliver cleaner and more secure and reliable energy for Australians.

- The Government will provide $102.2 million over four years to establish a Community Solar Banks program for the deployment of community-scale solar and clean energy technologies. Funding will improve access to clean energy technologies in regional communities, social housing, apartments, rental accommodation, and households that are traditionally unable to access rooftop solar.

- $45.8 million over six years from to restore Australia’s reputation and increase international engagement on climate change and energy transformation issues. This funding will allow for leadership and engagement in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

- $275.7 million over four years and $60.5 million per year thereafter to support establishing a strong Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. The department will facilitate the smooth transformation of our energy system, capture the opportunities of a clean energy economy, help protect, restore and manage Australia’s environment and heritage, and improve the health of our rivers and freshwater ecosystems.

- $630.4 million over four years to strengthen Australia’s resilience to disasters. This includes $200.0 million per year for the Disaster Ready Fund to co-contribute to projects nominated by state and territory governments to strengthen Australia’s resilience to disasters.

- Jobs and skills

- $43.2 million over four years from 2022–23 and $11.1 million per year thereafter to update workplace laws to get wages moving, boost job security, address gender inequity and create more opportunities for Australians.

- $76.4 million over four years for outcomes from the Jobs and Skills Summit to help build a bigger, better trained and more productive workforce, boost real wages and living standards.

- Education

- 480,000 fee free TAFE places in industries and regions facing skills shortages at a cost of $871.7 million over five years.

- $485.5 million over four years to fund 20,000 additional university places to help alleviate skills shortages in engineering, nursing teaching. Positions are dedicated to under-represented students, including first nations peoples, and students from regional and rural Australia.

- Health

- Expanding the medication listings covered under the pharmaceutical benefits scheme (PBS) including antiviral COVID treatments, multiple sclerosis, and cancer at a cost of $1.4 billion over four years.

- $787.1 million over four years to fund the ‘Plan for Cheaper Medicines’ which will reduce the general patient co-payment for treatments covered under the PBS.

- $808.2 million in 2022-23 to extend the Government’s response to COVID-19 until 31 December 2022 including co-funding state government programs such as vaccine delivery, testing and treatments.

- An additional $437.4 million will be provided over four years to expand funding for the operation of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

- The Government will provide $24.3 million over four years including $6.6 million per year thereafter to improve access to mental health services.

- Housing

- $350.0 million over five years from 2024–25 to support funding of an additional 10,000 affordable homes under a housing accord with state and territory governments and other key stakeholders.

- $324.6 million over four years from 2022-23 to establish the Help to Buy scheme to assist people on low to moderate incomes purchase a home with an equity contribution from the Government.

- Infrastructure

- An additional $8.1 billion over ten years from 2022–23 for priority rail and road infrastructure projects across Australia. Including:

- $2.6 billion for projects in Victoria, including $2.2 billion for the Suburban RailLoop East.

- $2.1 billion for projects in Queensland, including $866.4 million for the Bruce Highway, $400.0 million for the Inland Freight Route upgrades, $400.0 million for Beef Corridors and $210.0 million for the Kuranda Range Road upgrade.

- $1.4 billion for projects in NSW, including $500.0 million for planning, corridor acquisition and early works for the Sydney to Newcastle High Speed Rail, $268.8 million for the New England Highway – Muswellbrook Bypass and $110.0 million for the Epping Bridge.

- Manufacturing

- $135.5 million committed over four years to continue to support Australian industry to develop domestic manufacturing capabilities and upskill the manufacturing sector workforce.

- This includes $113.6 million to support local industry to secure and support new jobs and strengthen key manufacturing capabilities in regional areas.

- Regional Australia

- The Government will provide $5.4 billion over seven years to support economic growth and development across regional Australia. It includes:

- $1.9 billion in equity investment for the development of the Middle Arm Sustainable Development Precinct in the Northern Territory.

- $1.0 billion for the Priority Community Infrastructure Program to support community infrastructure projects across Australia, including $120.0 million to deliver the Central Australia Plan.

- $1.0 billion for the Growing Regions Program and regional Precincts and Partnerships Program to support community and place-based investment in rural and regional Australia.

- Women

- $169.4 million over 4 years and $55.4 million per year thereafter to provide an additional 500 frontline service and community workers across Australia to increase the support available for women and children experiencing family, domestic and sexual violence.

- The Government will provide $42.5 million over 4 years and $10.2 million per year thereafter to implement its response to recommendations of the Respect@Work Report.

Revenue measures and savings

- Multinational Tax

- Generate an additional $970 million of tax revenue from multinationals over the forward estimates by clamping down on the tax treatment of multinational corporations. The revenue benefits are not expected begin until the 2024-25 financial year.

- Measures include supporting the OECD’s 15% minimum effective global tax rate, limiting debt related deductions to 30% of profits, cracking down on the use of ‘tax havens’ and enforcing public reporting on tax contributions and beneficial asset ownership.

- The Government will provide $73.2 million over 4 years to incentivise pensioners to downsize. The measures will reduce the financial impact on pensioners looking to downsize their homes and free up housing stock for younger families.

- Tax avoidance measures

- Extending and boosting funding for the existing ATO tax avoidance taskforce and shadow economy compliance program to reduce tax avoidance. The program is expected to improve the underlying cash balance by $3.1 billion.

- Share Buy-back Tax treatment

- The integrity of the tax system will be improved by aligning the tax treatment of off-market share buy-backs undertaken by listed public companies with the treatment of on-market share buy-backs. This is expected to increase tax receipts by $550.0 million over four years.

- Electric car discount

- From 1 July 2022 battery, hydrogen fuel cell and plug-in hybrid electric cars will be exempt from fringe benefits tax and import tariffs if they have a first retail price below the luxury car tax threshold for fuel-efficient cars. This measure is expected to decrease tax receipts by $410 million over four years.

- Superannuation

- The Government will reduce the minimum eligibility age for downsizer contributions from 60 to 55 years of age. The measure will have effect from the start of the first quarter after Royal Assent of the enabling legislation.

- The downsizer contribution allows people to make a one-off post-tax contribution to their superannuation of up to $300,000 per person from the proceeds of selling their home.

- The measure is expected to decrease tax receipts by $20.0 million over four years.

Commentary provided by St.George Economics

Source: BT